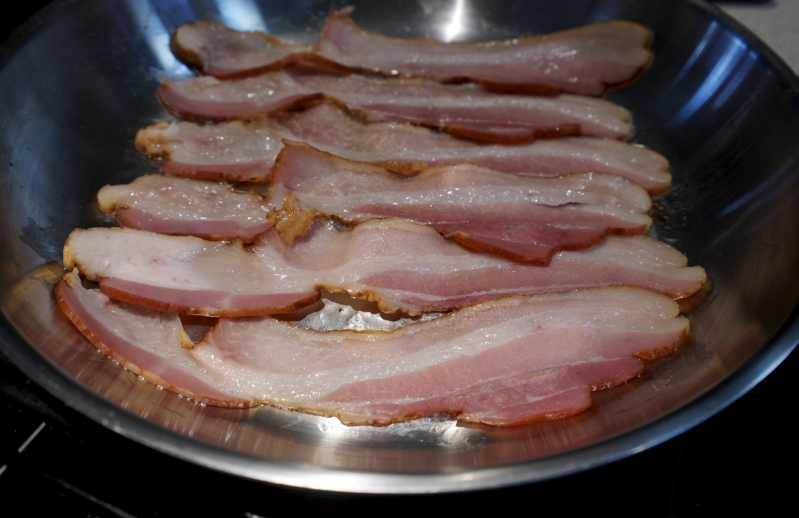

California is examining new World Health Organization findings to determine whether to add red meat and foods like hot dogs, sausages and bacon to a cancer-alert list, setting the stage for a potential battle with the meat industry over warning labels.

The inclusion of meat and processed meat on the list could reduce consumer demand, hurting major producers and processors like Hormel Foods Corp and JBS USA. It could also open the door wider for litigation against meat companies from consumers diagnosed with certain types of cancer.

California has often been at the forefront of consumer-oriented initiatives, particularly regarding agriculture. It rolled out laws for larger chicken cages and restrictions on antibiotic use for livestock ahead of much of the rest of the country.

Now the meat industry is focused on what the state will do after a unit of the WHO on Monday said processed meat can cause colorectal cancer in humans. It said the risk of developing cancer is small, but increases with the amount of meat consumed. The meat industry maintains that its products are safe to eat as part of a balanced diet.

California's Proposition 65, an initiative approved in 1986, requires that the state keep a list of all chemicals and substances known to increase cancer risks. Producers of such products are required to provide "clear and reasonable" warnings for consumers.

Some Proposition 65 experts expect California to add processed meats to the list. Typically, once an item is added, it is up to the maker to prove to the state that its product is not dangerous enough to warrant a warning label, experts say.

Starbucks Corp is embroiled in a lawsuit filed by a non-profit group in California over whether its coffee contains enough of the carcinogen acrylamide to pose a cancer risk, and should be labeled accordingly under Proposition 65.

The meat industry is adamant it will escape having to put warning labels on packages of bacon or hot dogs. It says a 2009 California appellate court ruling confirmed federal authority over labels for meat from plants inspected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

"Meats will never have to be labeled in the state of California," said Jim Coughlin, a consultant hired by the National Cattlemen's Beef Association. Still, he thinks processed meats will make it onto the Proposition 65 list.

The situation on labeling processed meats is not known, according to the state agency assessing the WHO findings, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment.

Federal law pre-empts warnings on fresh meat, but "our understanding of how federal law governs processed meats is less clear," Allan Hirsch, chief deputy director of the California office, told Reuters.

"We can't tell you if Proposition 65 warnings would be pre-empted if processed meats were added to the Proposition 65 list."

Labeling would be a bigger blow to meat companies than inclusion on the Proposition 65 list because labels could confront consumers front and center at stores and restaurants, say industry analysts. It is not known exactly what warnings might say.

The WHO's International Agency for Research on Cancer put processed meats in its "group one" category, along with tobacco and asbestos, products for which the agency says there is "sufficient evidence" of cancer links.

Any move to add red or processed meat to the Proposition 65 list would be challenged by the industry, said Mark Dopp, senior vice president of regulatory affairs and general counsel of the North American Meat Institute (NAMI).

The institute represents companies including Cargill Inc, Tyson Foods Inc and Kraft Heinz Co.

"The state can't force a label on federally inspected product," said Janet Riley, president of the National Hot Dog & Sausage Council and a NAMI senior vice president.

But a legal fight could follow. Private lawyers, or even the state of California, could file lawsuits in an attempt to overturn the 2009 ruling and force meat companies to apply labels, Coughlin said.

If that happens, NAMI "would wave the court of appeals decision. It'd be a stupid suit to even try to initiate because it's already been decided," he said.

Red meat is less likely to be added to California's list because it was classified as "probably carcinogenic," Coughlin said. That put it in the WHO unit's "group 2A" category, joining glyphosate, the active ingredient in many weedkillers, made by Monsanto Co.

Since the WHO's classification of glyphosate in March, Monsanto has faced a slew of lawsuits from personal injury law firms around the United States that claim the company's Roundup herbicide has caused cancer in farm workers and others exposed to the chemical.

In September, the California environmental office gave notice that it intended to list glyphosate under Proposition 65.

Monsanto has asked state officials to withdraw the plan, arguing that California's actions could be considered illegal because they are not considering valid scientific evidence.

(Reporting by Tom Polansek and P.J. Huffstutter in Chicago; Editing by Leslie Adler)