Friar Junipero Serra was an 18th century missionary who founded nine of California's 21 Catholic missions and is considered one of that state's founding fathers. However, a new book is shedding light on how his interactions with local Native American tribes have led to his current polarizing status.

According to Nick Welsh of Santa Barbara Independent, new interest in Serra has received the attention of Pope Francis, who wants to fast-track Serra for canonization to sainthood. A team of historians at Santa Clara University, Rose Marie Beebe and Robert M. Senkewicz, looked at what drove Serra through his "vast trope of reports and letters, many of which are kept at Santa Barbara's Old Mission Archives."

"A lot of stuff on Serra, he's presented in one extreme or the other: selfless, magnanimous saint or genocidal-maniac-type person," Senkewicz said. "We thought let's try to avoid the extremes and take him on his own terms and see where that leads us. That turned out to be something that hadn't been done about Serra."

Beebe and Senkewicz focused on Serra's contributions in the book Junípero Serra: California, Indians, and the Transformation of a Missionary. Welsh reported that the book painted a more complex picture of the friar.

"Together, they manage to conjure a more complicated, intriguing human being than the Junípero Serra extolled by supporters or vilified by critics," Welsh wrote. "Those searching for a clear and tidy resolution should look elsewhere, but for those comfortable with the clutter of human complexity, their book is a major contribution."

Senkewicz told Welsh that their approach on Serra "allows us to see him as a much more complicated, complex kind of figure."

"He's an administrator, so he writes a lot of boring bureaucratic stuff," Senkewicz said. "Unfortunately, that tone in previous translations seeps into letters that are personal. We tried to separate those so when he's writing another missionary or the governor, his emotions come out."

Welsh asked Senkewicz why a 55-year-old Spanish priest like Serra would want to go to Mexico to be a missionary. Senkewicz pointed out that Serra grew up in the Spanish island of Majorca, located "at the intersection of a lot of trade routes in the Mediterranean."

"A bunch of people there had been missionaries among the Muslims in northern Africa; there was a missionary tradition," Senkewicz said of Majorca. "So when Serra begins to have this personal crisis in his mid-thirties - I resisted calling it a midlife crisis because that's too Freudian - he's not happy. He's gotten to do everything he's going to get to do."

Welsh pointed out that Serra was an agent for the notorious Spanish Inquisition.

"He was forward-looking in some ways, but in others he always looked backward. He was an investigator of the Inquisition," Senkewicz confirmed.

Based on his research, Senkewicz thought that Serra had a "notion that he was always right."

"He was an impatient guy, very self-assured. Probably overly self-assured," Senkewicz said of Serra.

Senkewicz also told Welsh that Serra had a tense, hostile relationship with military commanders. The friar accused the Spanish military of raping Indian women and exploiting native labor.

"The relationship between missionaries and soldiers was always strained," Senkewicz said. "Missionaries tended to regard themselves as the friends of the Indians, and they tended to think the Indians were their friends, too. The presence of soldiers at a mission was a visible sign that this self-image was incomplete."

Senkewicz acknowledged that while soldiers certainly mistreated Indian women, he thought that Serra's writing exaggerated some of the events.

"The fact is they needed soldiers, they knew they needed soldiers, but they didn't like the fact," Senkewicz said of the missionaries. "My own sense is they probably blamed the soldiers for too much."

Welsh asked Senkewicz, a former Jesuit priest, on his thoughts about the Catholic Church making Serra a saint. Senkewicz noted that he can see "both sides of this issue."

"The pope is from Latin America; the major person in the U.S. pushing this is Archbishop [José] Gómez of Los Angeles, who was born in Mexico," Senkewicz said. "They're very interested in having a missionary Hispanic saint who brought the gospel to a new area of the world."

However, Senkewicz pointed out that there may be a few problems elevating Serra to sainthood.

"Serra was in so many ways a man of his time. He doesn't go beyond his time like Mother Teresa," Senkewicz said. "Also, if you canonize Serra, then you're canonizing the whole mission system, and that system was very much of a mixed bag."

From the lens of history, Senkewicz told Welsh that the missionary system was very different during Serra's time. He contended that Serra was "a colonial official."

"The missionaries' salaries were paid by the government. They were part of the Spanish colonial system," Senkewicz said. "Nowadays, the church missionaries wouldn't act like this. They'd try to understand native cultures a lot more, but back then, the Spanish empire had military and religious aspects to it."

In his final question, Welsh asked Senkewicz what influence Serra left on the development of the California Alta. Senkewicz cited Serra's pushiness, determination, and commitment as big factors.

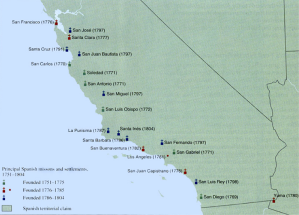

"He wasn't going to wait. Some other missionary may have waited," Senkewicz said. "He founds eight missions in the first eight years. Someone else might have said two or three would have been fine."

Senkewicz's book on Serra is available now both in bookstores and online.