"For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul? Or what will a man give in exchange for his soul?" Matthew 16:26

Technological advances, whether it's personal gadgets and computing devices, search engines, relational databases, or social media, have collectively enhanced and revolutionized the ways the world communicates, conducts business, and accesses information. Nested in the Silicon Valley of San Francisco Bay Area are the tech giants - Google, Apple, Facebook, Yahoo, LinkedIn, Instagram, Microsoft, Oracle, Adobe, Cisco, SAP, HP, Intel, Nvidia, Motorola, Salesforce, eBay, and Paypal - that are on the cutting edge of technological innovation and pay a hefty sum to employ the best of talent. In the midst of the heavy work demands and rapid industry transformation, how can a Christian be both ambitious and lead a God-honoring life without sacrificing faith and family?

"You have too much choice. It's hard for you to understand what's important," shared Mike Seashols, 68, citing his Congolese Christian friend from the Democratic Republic of Congo. "I'm going to pray for you extra hard. You live your life making choices. For us, our choices have been made. You're focused on what car and what house you'll buy, who your friends will be. You have mobility, resources, and it's very confusing. It's hard for you to understand what's important. Your spiritual life is part time. Ours is survival."

For many in the tech industry, Mike Seashols is a familiar name. He has played a pivotal role in several significant new technology and application "tipping points," including establishing Oracle as the leader in the emerging relationship database market with its impressive sales growth and IPO in 1986. His experience at Oracle was critical to the birth of many multi-billion dollar enterprise application companies, including SAP, PeopleSoft, Siebel, and others. Subsequently, he has served as CEO and Board roles in a number of successful technology companies, including Versant, Documentum, Evolve Software, GoldenGate, PostX, Avolent, Netbase, and more.

For many in his church at Peninsula Covenant, Seashols is also a familiar name. He has served in various roles in his 45 years at the church, including elder, deacon, small-group leader, and teacher. For his family, he is a committed husband to his wife of over 50 years, a father of two grown children, and a grandfather to more. Despite his success and notoriety, Seashols is approachable and doesn't forget to pray before a meal. He sat down with The Gospel Herald in Mountain View, Calif. for an interview, where he talked about his views on Christian living as an entrepreneur, including learning to be content, putting God and family first, and serving locally and globally.

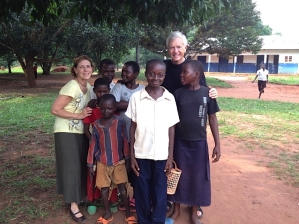

About three years ago, Seashols visited Congo, which led to his co-founding of CongoVoice, a non-profit which focuses on providing for the basic needs of children without families, educating/training the local population to become entrepreneurs in the midst of 95 percent unemployment rate, and supporting them to create a sustainable local economy. While Seashols has built companies from zero to sustaining billions, he has also received invaluable insights as he works at building and improving the lives of those in Congo.

GH: Can you tell me about your upbringing and how you became a Christian?

MS: It is interesting. We had six Congolese here being trained in a combination of things, but leadership training was certainly one of the responsibilities that we feel that we need to invest in. We have two women and four men. They are combination of doctor, a pastor, a farmer, a manufacturer, and educator. We bring them here for three months for a combination of English-speaking development, entrepreneurship, leadership, and management style. We had them over for dinner, and they asked, "What were some of the event in your life that have shaped you?"

Three particular events have shaped me. I grew up in a Christian family; we were Baptists. At eight years old, I went to my dad and mom and I said, "You know, I'm going to go forward this coming Sunday and accept Jesus as my Savior, and I wanted you to know." They said, "Well, are you sure?" and I said, "Absolutely." They would challenge me, because they wanted that decision to be mine, not something that was inherited from them of from my environment. So I went forward, and I remember it distinctly, because that was the first decision that I made entirely on my own, and it really changed the trajectory of my life. My priorities changed, my passion, everything.

The second event happened when I was 17, and it was when I saw my wife the first day at college. We went to a Church of the Brethrens College, and I went up and introduced myself to her, and after talking for three hours, and I asked her to marry me. She was 17, I was 17, and we'll be married for 50 years next year. That gives you some indication about my personality; I'm an aggressive, decisive sort of guy.

The third thing occurred with a man I'd be mentoring for twenty years, a young Christian man I'd met at church. We were colleagues in business, and I'd been quite vocal that I didn't have time to go to the Congo, I didn't have the passion to go-I felt fulfilled and focused with what I was doing here. He took me to breakfast three and a half years ago, and said, "Mike, you're going to the Congo." This was a total role reversal, where the mentored was telling the mentor, "This is something you need to do, because God's calling you." I went home and told my wife, and she started crying and said, "I've been praying for 5 years that you'd go to the Congo." And she went with me. When I went to the Congo, God fulfilled a need in my heart to serve, not give, and help people develop a resilient, can-do attitude in the face of extreme poverty and oppression. I taught a class over there at a school that was being formed, and my life was never the same. That's when we came back to the states and formed CongoVoice, which my wife named, because we wanted to draw attention to the oppression and other extreme difficulties going on over there.

GH: I understand that you want to share as much as you can about the needs of those in Congo, but can you share with us more about your career at Oracle. I read an interview by Fast Company that you've been a very family-oriented person, and that you would go home by seven o'clock when your wife called. How has your faith influenced you in your career, relationship with others, and your family?

MS: The one thing about Christianity is that I don't think it should be compartmentalized, whether it's in your personal life, your athletics, or your business career, or your service life, or your family life. Once we started having children, we said we'd never move. So we've lived in the same house for 43 years. We've raised our children in Christian home, but they had to make their own decision. They both confessed Christ early, but they both have all walked their different paths since then. It's always been a priority for us to create a Christian environment, a service environment, a safe environment. Weekends were sacred, family dinners were sacred, we made family vacations every year a high priority, and they were always adventure over entertainment. We'd travel all over the world, we'd go to Taiwan, Thailand, Nepal, Costa Rica, Australia-you name it. As a family, we exposed the kids to the corners of the world to the point where our oldest son, at about age 25, had made a little bit of money as an entrepreneur and left for two years backpacking the world because he wanted to know what the world was like. He is one of those guys who would sleep on the bus bench and meet somebody and stay at their home and get into their culture. His brother went with him for a year. So you can talk with them about anything in the world, and they feel comfortable talking about it having been there.

Another important thing for us was serving within the church and serving within missions in that church. We've attended the same church for over 40 years; we've each had roles as teachers, leaders, whether it's a trustee or an elder. We've always had small groups, because in there, life is safe, and you can share personal struggles. We've always had individual same-sex groups; couples groups are also great environments. On this end of life, God's protected us-we've had different difficult events in our life, we've had challenges from our youth we've struggled with, but we process through it. I consider my two sons to be good friends as well as sons. We all struggle with life together.

GH: During your time at Oracle in the 80s, you've had a conversation with Oracle CEO Larry Ellison over a meal, and he asked you what you want to do next after making all the money as Oracle continues to develop into a multi-billion dollar tech giant. In response, you said that you just wanted to be content. He was taken aback by your statement. Can you explain why you gave that reply?

MS: Early on, I spent over ten years at IBM, had a successful business career, had started two companies, and had made a little bit of money before Oracle. When I was joining Oracle in my mid 30's I'd already had some success and notoriety. Larry really hadn't. We'd both grown up the Midwest, I was driving a nice car, and he was driving a Mazda. I had a family and a nice home. He was still developing, and married to Barbara then. He was still not prioritizing family really high. I think he was intrigued, because we were the same age and both computer guys, so we developed a very close friendship. But Larry was always driven not only by success, but also a win-lose mentality, and mine was always win-win. Mine was always, "Lord, don't give me so much, that I'll lose my passion for you." I'd seen enough where wealth became people's objective rather than growth in Christ or in the church. Larry was still trying to prove to himself wealth was the scorecard, that he was going to be driven by wealth. Mine was just enough to where I don't have to steal, but not too much.

We live in a very comfortable world, but most people don't. In this comfortable world, you have to decide how much comfort is going to drive you. After a certain point, wealth won't change your comfort level, but it will affect your pride and your ego versus your humility and service and contentment. I think Larry couldn't quite understand that. To this day-I talked to him a couple weeks ago, he doesn't understand, and here is he is a multi-billionaire. Where does it stop?

GH: As a friend of Larry, do you know if his philanthropic giving is influenced by his friends?

MS: I hope so. We're living in tremendous wealth attainment in this area, but Gates, Bono and other guys are saying "What's it all for?" At a certain point, there's nothing to spend it on. You can buy islands in Hawaii, as Larry has, or planes, or basketball teams, but eventually you have to say, "Where can I give back and serve?" So I would hope that one thing I've learned from CongoVoice is that giving sometimes hurts more than it helps. So, if you're not a wise philanthropist, you're really creating more harm than good. Just like in any business strategy, you've really got to know the dynamics of how to invest and sustain it, and be wise about it. I think that Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is doing a really good job of figuring out, with that amount of wealth, how to invest in the fundamentals. Clean water is a fundamental, freedom is a fundamental, choice is a fundamental, and order is a fundamental. When we started CongoVoice, we said, "Ok, let's create a focus on geography. We first focused on the Congo, and then a smaller region within the Congo, and then we focused on the most needy, which was the orphans dying on the street. We took the orphans into a student environment, because we have to develop sustainability for them, give them hope and opportunity. That's when we started integrating the focuses on children and students. Because there is no job, the students don't become workers, they become entrepreneurs. You don't get a job when there is no job. You create a job. Within that geography, with the amount of money that we're able to attract and deploy, we can then develop a sustainable model that lives beyond CongoVoice.

Saying that, when Larry is giving away billions of dollars, you've got to make sure you don't put into a place where you just create dependency or a cliff, or else there could be a catastrophe. There is an art to that. There are some really smart guys that are figuring that out.

GH: As a close friend to Larry, have you tried sharing the Gospel with him?

MS: Oh, absolutely. He knows the Gospel. He had Bibles in his library, and early on, would talk freely about it. He was very interested. He's a spiritual guy, but I think that's been channeled into the Eastern spirituality, like Buddhism. He's really intrigued with Japan. He doesn't really talk about it to me anymore. We've been vocal as Christians that this is what we believe to him--he's a very spiritual guy.

GH: There was a time when Larry eventually had to let you go from Oracle. Can you share with us about what happened that led to the breakup and what did you do afterwards regarding your business career? How did you deal with that from the perspective of faith?

MS: We were getting ready to go public, and I think the thing that probably broke our relationship was, even though we were both aggressive business people, there's a place where you don't cross the line. We would always laugh and say, "I'll put my toes on the line, I'll put my heels on the line, but I won't go over the line." And he would have a tendency to push harder, and I remember one time, we were working with the bankers. We would discuss the red herring, where we'd be writing out the business strategy, and we were off site. We almost got into a physical confrontation, because he would describe something, and I'd go, "That's just not right." And he'd say, "Are you calling me a liar?" and I'd say, "No, I'm saying what you're saying isn't true." It was a defiant time for us. We had a breakfast one day, and he said, "I don't want you to play anymore." I said, "Ok." This was at 9 am at Bucks Restaurant. By 11 am, everyone in the industry had known, and I had met with Bob Miner in the lobby, and we were crying together. He said, "I don't want you to leave." I said, "I can't get along with your partner." I went home, saw my wife, got a call at 1 pm from the CEO of our competitor, and he said, "Can you come over today?" and they hired me at 2 pm that same day. I didn't have too much of a downtime. Two years later, we took that company public. It was called Ingres. After that was when I started my own database company.

GH: Your experience reminds me of the verse from Revelations 3:7, "What God opens no one can shut, and what he shuts no one can open." How do you channel your experience as an entrepreneur and successful businessmen into your service locally in the Silicon Valley and in Congo? Also, I heard that the church that you attend in the Peninsula has a long-standing tie with Covenant Church in Congo, which boasts of over 200,000 members. Can you share about that as well?

MS: Being involved on a board level with very, very large companies, and also being an entrepreneur and starting companies from scratch, you can see what it takes to initiate and build something initially to where you sustain and grow and dominate it globally. I was fortunate enough to have traveled internationally, so I've seen the culture and business style from China to Russia to Europe to Italy. So having the perspective of starting from scratch and sustaining billions, you have a perspective that gives you the ability to say, "We can start something and have a global impact." When we joined the Covenant Church, we'd never had exposure to Covenant Church. My wife grew up Lutheran, I grew up Baptist, we went to a Church of the Brethren College, but God led us to this church. It's an Evangelical church with Swedish origins, but we've felt comfortable with its leadership. The church is a framework, and the real work occurs in the small groups and the missional aspect of the church, not within the constraints of the building. Our church always thought outside; we have a center to do outreach, with tennis and basketball and a swimming pool, we've always reached out to the community from East Redwood City to East Palo Alto. The breadth of our mission is way beyond the constraints beyond the building. We've always served in the Congo. That goes back to the 60's, when a Stanford graduate who went to our church and went to the Congo and to serve as a doctor Paul Carlson and was murdered. Our church embraced that; we've always had an affinity for this region of the Congo.

So, we then met some Congolese who had come here to the states for leadership development, getting their PhD's, and that's when we said, "Ok, let's start putting more emphasis on the ground." We started putting mission teams together that would go visit and take large containers of computer technology just to expose the area, because agriculture was the primary interest there. I think when I got personally called there three years ago, and there was so much available that you could build a big impact place there, because we had 250,000 people there that were Christians that went to 1,600 Churches there. The infrastructure, communication, collaboration there was in place, it just needed some more fabric of sustainability, economic development, education, medical services, orphan care, better communication, and clean water. My co-founder was the president of the denomination of the Congo, and now we partner with the new president of the Congo area, and we've just been saying let's use the infrastructure, because you can trust it and it's already there.

Government agencies there aren't as mature as the church agencies. The way the churches have become dominant in the Congo actually goes back to when the Belgians ran the Congo in the 30's and 40's. At the time, the Belgians gave Catholics, Protestants, the Free Church, Covenant Church a province of the Congo. They said they will develop central government, but we don't have time to develop agricultural business, educational and medical business in the remote area. The Covenant, along with the Free Church, was given the northwest corner called the Equitorial Province in the seven provinces in the 30's and 40's.

When the Belgians left in the 60's, the churches were the only stability. That's why we do the education, the medical services, the economic development and orphan care. We rely on other resources to do the order and justice, and so on.

GH: What are the most pressing needs there and the projects of CongoVoice?

MS: The foothold and structures are in place, but I'll give you two things: I'll give you a macro view, where CongoVoice partners, and a tactical view, which is where CongoVoice is focused on. On a macro view, we partner with Human Rights Watch, where they have sixteen people on the ground monitoring oppression and injustice, because that's still rampant. Sadly, it's not isolated to the Christians, and it's not tribal, it's economic. We partner with other organizations, like Paul Carlson Parntership, Doctors without Borders to make sure we have delivery of medical devices, we work a lot with the Chinese, Canadian and German government to put in roadways, re-establishing bridges so we can get distribution and access. Right now, you can't drive where we are; you have to charter a flight or go up a Congo River that would take weeks to arrive at your destination.

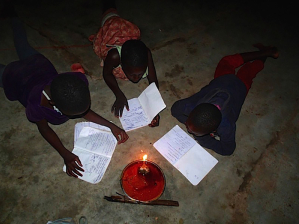

So what we've done tactically: we've drilled the water wells so you can have water access, we put in solar power so you can have lights and security, we put in refrigeration so you can have medical supplies and food. And the third thing is the internet. The internet gives you economic tools, and we're developing an IT team over there, which we're using it for education so you can do online training. It's hard to get a professor because there are no books. With the internet and projector, you can do quality online courses, for example, we partner with Stanford, etc. We're developing a whole new way to educate people--not with memorization and testing, but with development and collaboration. And then there's economic development. We save the orphan's lives, but there are hundreds that still need to be rescued, and 4 million in the country are dying. We have nurseries that are getting staff trained.

We also just introduced the Congo Animal Initiative funded by CongoVoice. If you think about the Congo today, it's like the West in the 1880's. There are no roads, no gas stations, so you can't use tractors. They farm how people did back then. So we've reintroduced oxen, which have run wild there, to be yoked for plowing and for transportation. We took a group of cattle trainers from Michigan to train people how to use these oxen, and we're transforming the area with oxen-powered globalization. That's what they need. Right now, a typical farmer can plow less than an acre because they have to tow the land by a stick, and they physically can't do more than that. If we can plow the land with oxen, we can now farm ten acres. We can now use oxen and plow ten acres, and build roads, and move heavy equipment and lumber. It's changing their lives.

GH: Many organizations are providing these resources, but one of the major factors that affect the continuous sustainability is the constant threat of violence and injustice. Has the rise of radical Islam affected some of the areas where you are serving?

MS: The violence and injustice in Congo is not a Spiritual war, it's an economic war. It's a combination of other countries coming in and the corruption within the system. Some of the people we're training here in the States are going to go back to the Congo and serve in government. You have to have social interaction as well as government interaction. We work a lot with the Human Rights Watch--they have sixteen people that are monitoring injustice; there's more corruption than violence. There has been some violence, and as an American man with white hair, you've got to be careful. But violence isn't our challenge right now. We're also respected for what we're doing and have been meeting with the minister of education for the country of Congo who's seen what we've done over the past several years. He has asked us to help promote across the country what we're doing with the educational model.

Our biggest challenge right now is accessing distribution and infrastructure. We can farm thousands of acres, produce quality crops of palm oil, coffee, or peanuts, but we can't get it to the market because there are no roads, airplane travel is too expensive and river travel is not reliable. Our next point of development is building roads and bridges to get access and distribution.

GH: In Rwanda, Pastor Rick Warren and his church Saddleback Church have been really involved in developing the country's infrastructure and educational system through the Purpose Driven Global Peace Plan. Have you ever looked at their model and consider ways that these two organizations would be able to work together? They are deeply entrenched in the country through government's direct support.

MS: Anybody who's an entrepreneur asks who's successful and why, and who's failed and why. I spend a lot of time with big organizations and entrepreneurial organizations trying to figure out what works. World Vision-we've partnered with them a lot-because they have great capacity and are smart and experienced. We work a lot with Mission Aviation Fellowship, which is not just airplanes in the area, but we partner with them to bring internet and drill wells. We partner with World Vision for education and orphan rescue. Everybody has their role.

With CongoVoice, we try to find the holes that the large guys miss. We work with smaller problems, a smaller physical area, and a smaller demographic, with 500,000 people in our area. They need to find a niche, and those niches might become large. What Saddleback is doing is tremendous. Our advantage is that our congregation gives us around quarter of a million Congolese.

As a Westerner, you cannot understand the market. You don't understand what it's like every day to wake up and be in survival mode. They don't have a concept of saving; they have a concept of surviving. They live their life tactically, it's every day. We think in weeks, months and years, but they don't have that luxury. You really just have to put yourself, as much as you can, in their shoes.

One comment that was insightful for me: I was saying goodbye to one of my dear friends from the Congo, and I asked him, "What would you share with me?" and he said, "I'm going to pray for you extra hard. You have too much choice. It's hard for you to understand what's important. You live your life making choices. For us, our choices have been made. You're focused on what car and what house you'll buy, who your friends will be. You have mobility, resources, and it's very confusing. It's hard for you to understand what's important. Your spiritual life is part time. Ours is survival." Very insightful. He had no empathy to say, "Wow, I'd love to live in America." No, it is like having too much. It goes back to Larry. You have too much; you don't focus on what's most important. Very insightful.

GH: Anything else we can pray for?

MS: Right now, pray for harmony between our Western mentality and the Congolese mentality. We're drivers, we're creative, and they live a life of harmony within their country, even though it's got extreme difficulties of poverty and hunger. We're in there trying to fix it, and we have to work through them, because if it's not sustainable, it won't work. Pray for priorities: what should we be doing next? Give us wisdom of where to put resources next. Pray for resources from the Western world; we have such access of resources, and so little has such an impact on them. What we spend for breakfast can feed a family for six months. Also, pray that people all over the world who have more than enough. Too much will not create contentment. Pray for contentment for us.

Visit CongoVoice.org to donate and support.