British scientists this month received permission to alter the DNA of human embryos within the overall mission of correcting devastating diseases in the womb. The work of one authorized stem cell scientist, using embryos donated by couples with a surplus after IVF treatment, will look at the fertilized eggs' development from a single cell to about 250 cells. The research could help scientists understand why some women lose their babies before term, and provide better clinical treatments for infertility, using conventional medical methods.

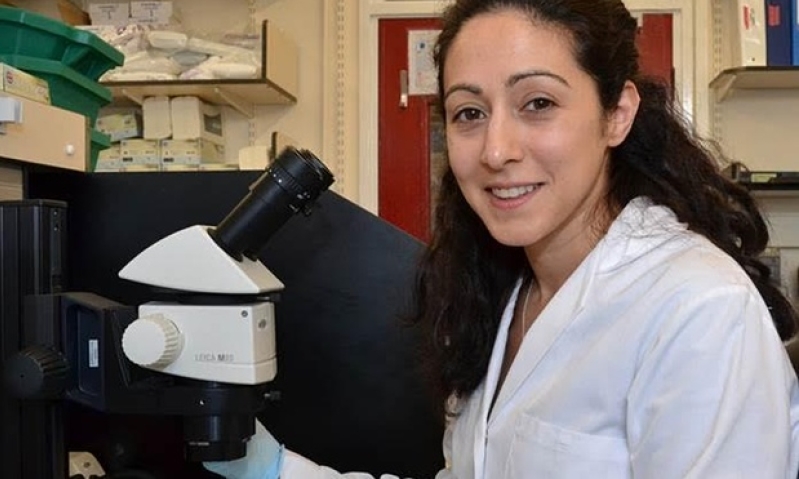

The Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA) regulating entity approved the license application by Kathy Niakan, a stem cell scientist at the Francis Crick Institute in London, to perform genome editing, or gene editing, on human embryos. The decision permits Niakan to study the embryos for 14 days for research purposes only, and does not permit them to be implanted in women, reports The Guardian.

"We are indeed playing God with our genes. But it is a good thing because God, nature or whatever we want to call the agencies that have made us, often get it wrong and it's up to us to correct those mistakes," stated Johnjoe McFadden in an opinion piece published in The Guardian on Feb. 2.

McFadden projects that of half a million babies born in the United Kingdom this year, about 4 percent will carry a debilitating disease or a genetic or major birth defect that could result in an early death. He believes Niakan's research can lead to technologies that could edit DNA to correct the mistakes before the child's development goes to its final draft. "Its successful implementation could reduce, and eventually eliminate, the birth of babies with severe genetic diseases," he wrote.

The decision to allow such medical research was supported by the Francis Crick Institute and some British scientists but was met with anger and dismay by those concerned that rapid advances in the field of genome editing are precluding proper consideration of the ethical implications.

Niakan will apply a genome editing procedure called Crispr-Cas9 to switch genes on and off in early stage human embryos. She then will look for the effects the modifications have on the development of the cells that go on to form the placenta, according to The Guardian.

Dr. David King, director of Human Genetics Alert, said: "This is the first step in a well mapped-out process leading to GM babies, and a future of consumer eugenics." He claimed the government's scientific advisers already were comfortable with the prospect of so-called "designer babies."

The HFEA now has the reputation of being the first regulator in the world to approve this uncertain and dangerous technology, said Anne Scanlan, from the anti-abortion organization Life. "It [HFEA] has ignored the warnings of over 100 scientists worldwide and given permission for a procedure that could have damaging far-reaching implications for human beings."

The U.S. National Institutes of Health does not currently fund any genome editing research on human embryos.

HFEA's ruling is a triumph for common sense, maintained Darren Griffin, a professor of genetics at the University of Kent. "While it is certain that the prospect of gene editing in human embryos raised a series of ethical issues and challenges, the problem has been dealt with in a balanced manner. It is clear that the potential benefits of the work proposed far outweigh the foreseen risks," he said.

Gene editing of human embryos to eliminate disease should be considered to be ethically the same as using laser surgery to correct eye defects, or a surgeon operating on a baby to repair a congenital heart defect. DNA is just another bit of our body that might go wrong, proclaims McFadden.

"If those of us with mostly healthy children are worried about the ethics of gene editing, then we should ask the parents of children born with hemophilia, cystic fibrosis or muscular dystrophy whether they would have used this kind of technology if it had been available to them," states McFadden.

"If science can be used to eliminate human suffering, then let's get on with it."