The awareness and support for the environmental movement has been a major issue in modern society that traces its origins back to Christianity. The former Archbishop of Canterbury contended that Christians should continue to "pull together" to tackle society's challenges, which included protecting the environment.

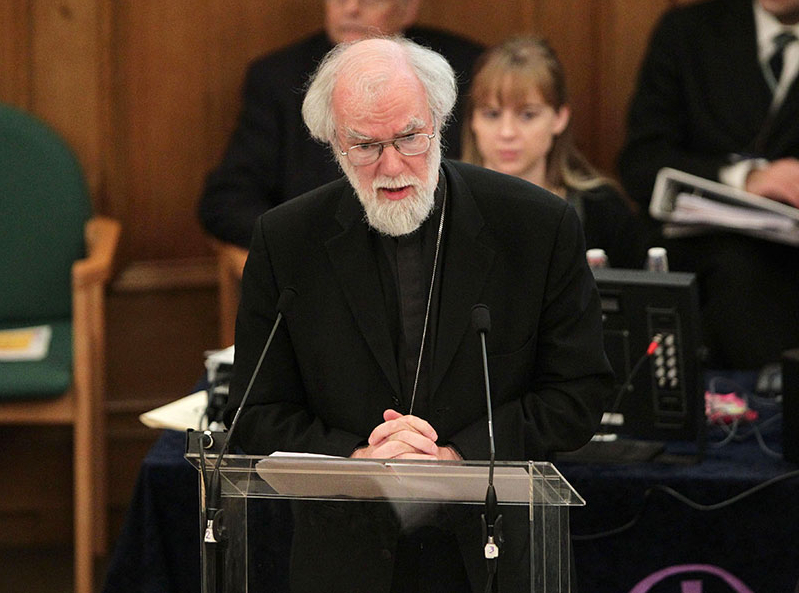

According to Jo-Anne Rowney of Catholic Herald, Dr. Rowan Williams highlighted various social challenges, which included increased poverty, violence, disease and environmental degradation. He made those comments in the United Kingdom city of Brighton on Sunday.

"Christians can respond together recognizing that any one group of Christians don't have the answer to all these challenges," Williams said. "When we do work together it's so much more successful."

Williams added that both Pope Francis and Justin Welby, the current Archbishop of Canterbury, expressed similar remarks on the environment.

"What I think will be very interesting in the next few years will be just, to pull together the social thought on which Christian compassion is agreed," Williams said.

Williams contended that communal response is not just limited to within the Christian churches. According to Rowney, he made those comments in context to the recent terror attack in Tunisia.

"We find that there's convergence and an echo in how other religions and religious traditions push back against the violence and the injustice in the world," Williams said.

Rowney reported that Richard Moth, the Bishop of Arundel and Brighton, agreed with the comments, noting that schools within the Catholic Church helped prepare young people to tackle such challenging social issues.

"We're enabling our young people to understand an ethos and a way of life that we can enable them to grow and be ever more open to that - that will transform society," Moth said.

According to Mark Stoll of Zocalo Public Square, the roots of modern environmentalism can be traced back to Christianity, in particular Presbyterianism. In an article published by Time, Stoll credited President Theodore Roosevelt of bringing that view of the environment to public consciousness in the United States through the Progressive movement.

"The blood of some ancestral Scotch Covenanter or of some Dutch Reformed preacher facing the tyranny of Philip of Spain was in his veins, and with his large opportunities and his vast audiences he was always ready to appeal for justice and righteousness," Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge said of Roosevelt.

Stoll found in his research of the Progressive movement that many of its leaders, including Roosevelt, had Presbyterian origins. Between 1885 and 1921, non-Presbyterian presidents held office for a little over eight years.

"Progressives grew up in an era in which big money corrupted politics, large corporations dominated the economy, and environmental crises threatened the natural world - forces that might rouse the ire of those on the 'blue' side of the spectrum today," Stoll wrote. "But the situation was a call to arms for those who were steeped in the Calvinist demand for a righteous society, a kind of moralizing that might be more considered on the 'red' side of the current spectrum."

Stoll observed that the progressives acted like "evangelicals out to spread righteousness in the nation."

"Censorious Presbyterians attacked greed and avarice with a special vengeance, as the sins that prompted Eve to reach for the forbidden fruit and exile us all from the Garden," Stoll wrote.

Stoll contended that this take on moral courage also drove environmentalism in the U.S. He looked at Calvinist churches, which had a strong interest in nature and natural history.

"To many Calvinists, nature study had an aura of sanctity as a moral occupation for men, women, and children alike," Stoll wrote. "God, they said, gave natural resources to humans to use for the common good, but not sinfully to waste or turn to greedy or selfish purposes."

According to Stoll, Roosevelt believed that government was responsible for protecting nature and natural resources against such attitudes. During his presidency, Roosevelt made "conservation" the cornerstone of his political agenda by expanding the National Park system and creating the first 18 National Monuments.

"Conservation is a great moral issue," Roosevelt said. "I believe that the natural resources must be used for the benefit of all our people, and not monopolized for the benefit of the few."

Stoll noted that after Roosevelt died in 1919, progressive Harold Ickes carried on his legacy. Not surprisingly, Ickes himself was a Presbyterian.

"Among his many acts as Secretary of Interior in the administration of Roosevelt's cousin Franklin, he desegregated the National Parks and added the first four parks intended to remain as undeveloped wilderness: Everglades, Olympic, Kings Canyon, and Isle Royale," Stoll wrote of Ickes. "His career was a fitting capstone to the great era of progressive Presbyterianism."