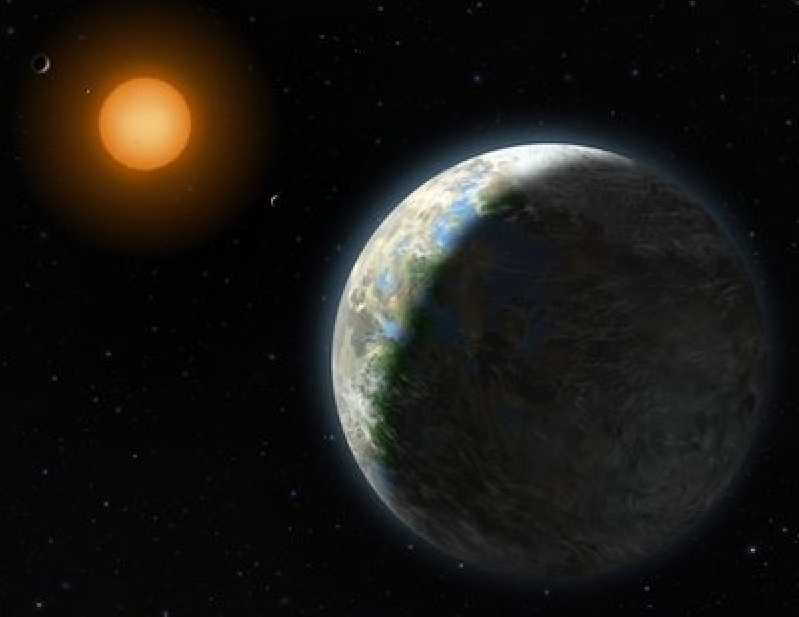

A team of planet hunters announced this past week the discovery of an “Earth-sized” planet that it said could be “potentially habitable” though one side of the planet is perpetually night and always freezing cold and the other side is perpetually day and always blazing hot.

"Our findings offer a very compelling case for a potentially habitable planet," said Steven Vogt, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz, who teamed up with astronomers from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Tennessee State University, and the University of Hawaii at Manoa for the search.

"The fact that we were able to detect this planet so quickly and so nearby tells us that planets like this must be really common," he added.

According to the astronomers, the planet, Gliese 581g, has a mass three to four times that of the Earth and an orbital period of just under 37 days. As the planet is tidally locked to the star it orbits, the side of the planet facing the star is believed to be almost always around 160 degrees while the side facing away is believed to be almost always around 25 degrees below zero.

Still, while the two sides alone might suggest the planet to be unable to sustain life, the team of astronomers say it is on the line between shadow and light that water – and thus life – could exist.

Vogt went as far as to tell the press "that chances for life on this planet are 100 percent."

"We had planets on both sides of the habitable zone – one too hot and one too cold – and now we have one in the middle that's just right," Vogt said, alluding to the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, from where the “Goldilocks zone” for life was penned.

"Any emerging life forms would have a wide range of stable climates to choose from and to evolve around, depending on their longitude," he added.

Notably, however, while many experts agree that Gliese 581g could be the most Earth-like exoplanet yet discovered and the first strong case for a potentially habitable one, there are also many who point out that there is much more needed for life to emerge than water.

“There’s a whole slew of conditions that need to be met for life to arise, particularly advanced life,” noted astrophysicist Dr. Jeffrey Zweerink, a research scholar at science-faith think-tank Reasons To Believe.

“It (water)’s a necessary requirement, but what we’re arguing is that the requirements for life are far greater than that,” he added in RTB’s Science News Flash podcast Thursday. “So simply because we find these, jumping to the conclusion that life is going to be there … assumes a whole like more things.”

In Zweerink’s opinion, there may be water on Gliese 581g, but there are not going to be the requirements for life as there are just “a whole lot of problems for this planet.”

In naming a few, Zweerink pointed to the tidal locking, the temperature issue, the magnetic field issue, the planet’s mass, the dense atmosphere, and the plate tectonics that are likely occurring on the planet.

“If your criteria is planets that could have liquid water in some capacity, then yeah, I’m going to expect that we’re going to find a lot of planets like that. That doesn’t surprise me at all,” he said when asked for a response to claims that there could be billions of planets with water on them.

“But again, that’s not the real question,” the astrophysicist added. “The real question is ‘Is liquid water the minimum requirement that life requires and given that requirement that life arises or does life require something much greater?’”

Adding to that, RTB Founder Dr. Hugh Ross noted how “many of these astronomers … are assuming if they’ve got a planet that has water that it’s automatic given that you’re going to have bacteria there.”

“Well, it is if the origin of life is an easy naturalistic step under liquid water conditions. But anyone who has studied origin of life research recognizes that that’s definitely not the case,” he pointed out. Ross and his colleagues assert that there are at least 300 conditions that need to be met for even simple bacteria to exist on a planet and at least 900 for more advanced forms of life.

That’s not to say, however, that RTB scholars are not excited about the latest discovery. In fact, they are.

Zweerink, for example, noted that Gliese 581g does meet more than just the minimum requirements for life and is like Earth “in a couple of minimal ways.”

“And if we can ever develop the technology to be able to determine ‘Does this planet have life on it?’ or ‘Can we find life signatures?’ that will help us test which of these models is correct,” he added, referring to two models for the origin of life.

One of the models – the more popular one among scientists – supposes that life arises under minimal circumstances while the other suggests that life requires extreme fine tuning of the environment and even divine input to get the whole process started.

“I’m excited about what we’re going to find in the future,” Zweerink noted before pointing out the developments in astronomy over the past 15 years – from when no planets were known outside Earth’s solar system to the now over-500 that are known.

“Now we’re at that place where we’re just beginning to find planets in the habitable zone. Presumably, we’re going to find a lot more in the next 15-20 years, so we’re going to be able to test this a lot more thoroughly,” he added.

That said, RTB is looking forward to hearing more from the team led by UCSC’s Vogt and Paul Butler of the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

According to team member Nader Haghighipour from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, the planet hunting team is keeping tabs on many nearby stars using the W.M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea and collecting more and more data about how the stars are moving.

The astronomers, he reported, expect to find many more planets with potentially Earth-like conditions.

Haghighipour also noted that to learn more about the conditions on these planets would take even bigger telescopes, such as the Thirty Meter Telescope planned for Mauna Kea.

To discover Gliese 581g, the team looked for the tiny changes in the velocity of its star that arise from the gravitational tugs of the orbiting planets. They used 238 separate observations of the star, Gliese 581, taken over a period of 11 years.

While astronomers describe the Gliese 581 system as being relatively nearby, in actuality, the system is about 120 trillion miles away. To get there, it would take several generations by spaceship.