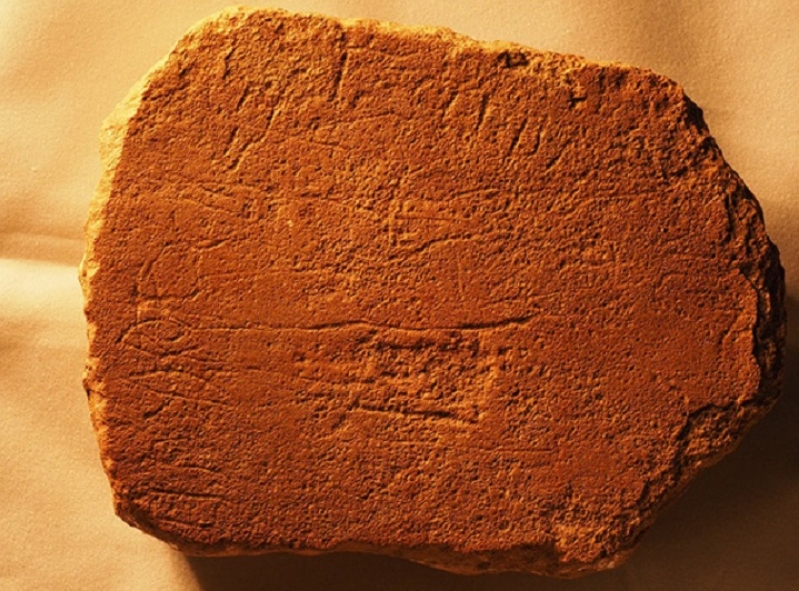

An archaeologist and epigrapher who has been studying inscriptions on stone slabs found on several Egyptian sites wrote a study suggesting that these inscriptions show Hebrew is the world’s oldest alphabet and could prove the Biblical basis for the Exodus.

The inscriptions are an early form of Hebrew, according to Douglas Petrovich of Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada, who spoke at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research on Nov. 17, Science News reported.

He said the Hebrew speaking Jews simplified the Egyptians’ hieroglyphic writing system to make it easier to communicate with them in writing, and the result was 22 letters that could be the world’s first alphabet.

Petrovich said he stumbled upon the word “Hebrews” while studying a text dated 1874 B.C. that contains the earliest known alphabet (scholars believe the Jews stayed in Egypt only from 1876 B.C. to 1422 B.C.). He combined some known letters from this old alphabet system with his own list of disputed letters to identify the text as Hebrew.

From there, he was able to translate 18 Hebrew transcriptions from the stone slabs.

“There is a connection between ancient Egyptian texts and preserved alphabets,” Petrovich said.

Interestingly, his translation revealed the names of Joseph, son of Jacob who was sold into slavery and eventually became a powerful governor in Egypt; Asenath, Joseph’s wife; Manasseh, Joseph’s son; and Moses, God’s chosen deliverer for the Israelites, whom he led out of Egypt.

One inscription read, “The one having been elevated is weary to forget.”

Another read, “The overseer of minerals, Ahisemach.”

Petrovich’s work appears to show evidence of the Biblical account of the Exodus, which, so far, has not been proven with evidence other than the ancient Scriptures.

“The biblical narrative of an extended Israelite stay in Egypt and a spectacular mass exodus under the nose of pharaoh long has been the laughingstock of ancient Near Eastern scholars, as no evidence of any of these events outside the biblical narrative has been presented. These days are coming to an end,” Petrovich wrote in an article published in 2013.

His claims had been hotly contested by other scholars, who argue that the Israelites were not present in Egypt as early as Petrovich proposed. Many scholars also believe the ancient text Petrovich studied could be any of the old Semitic languages.

Petrovich is now finishing a book detailing his findings and analyses of the inscriptions and showing how an ancient form of Hebrew can be used to understand Egyptian inscriptions. His book, funded through Kickstarter, is expected to come out in a few months.