The Bible is the story of immigrants, stated Joel Baden, Hebrew Bible professor at Yale Divinity School, in a Washington Post opinion-editorial, proclaiming outsiders should be treated with Biblical-driven respect and care when it comes to U.S. immigration policies.

Baden said when evangelist Franklin Graham declared President Donald Trump's travel ban was "not a Bible issue," Graham "could not be more wrong."

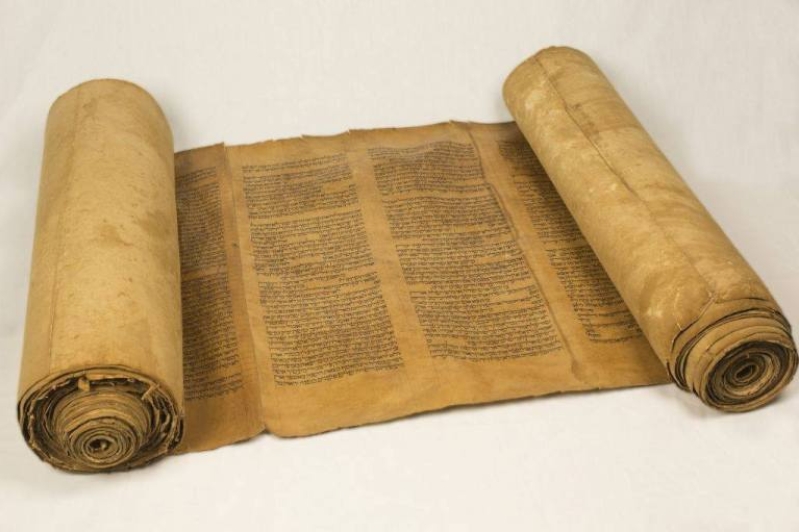

Baden's op-ed was published Feb. 10. He said for the nearly 80 percent of Americans who, according to some studies, believe the Bible to be divinely inspired, what this culturally foundational document -- the Bible -- says about immigration, foreigners and the treatment of the stranger, defined in biblical terms as any person who dwells in a land without being a citizen of that land, is "not simply a matter of historical record; it should inform us today."

The book of Genesis narrates the journey of Abraham from his homeland to Canaan, a land that is already occupied by other people, and recounts the story of how he and his family make their way in a territory and society that is not their own, where they have neither land nor kin, starts Baden.

"Both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament are clear and consistent when it comes to how we are to treat the stranger," penned the professor.

"Across the books of both testaments, in narrative, law, prophecy, poetry and parable, the Bible consistently spells out that it is the responsibility of the citizen to ensure that the immigrant, the stranger, the refugee, is respected, welcomed and cared for. It is what God wants us to do, but it also recognizes that we too were immigrants - and immigrants we remain. 'Like my forebears, I am an alien, resident with you,' says Psalm 39.'"

Baden references that the Exodus story reinforces the status of Israel as strangers in a land not their own. Pharaoh's oppression of Israelites is grounded in an attitude that might sound eerily familiar: "The Israelite people are too numerous for us," he tells his subjects, "let us deal shrewdly with them, so that they may not increase, otherwise in the event of war they may join our enemies in fighting against us." Pharaoh was skilled at governing through fear.

Israel leaves Egypt as refugees, and encounters nations that, out of fear or sheer intransigence, do not want to let them pass, forcing them through the harsh wilderness, states Baden.

"In the New Testament, Jesus and his family become political refugees, according to the Gospel of Matthew," writes Baden. "Perhaps the most salient biblical narrative on this topic is the book of Ruth. Ruth includes the story of a foreigner who comes to Israel, working as laborer in the fields, hoping for a better life. And it is this foreigner, immigrant and stranger, who turns out to become the ancestor of King David, and, through him, Jesus."

All three of the great law codes of the Hebrew Bible in Exodus, Leviticus and Deuteronomy contain the same command regarding the treatment of the stranger, states Baden: "When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not wrong him. The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt (Lev. 19:33-34)."

The Golden Rule - "Love your neighbor as yourself" - carries equal weight with the stranger, declared Baden. "You shall not subvert the rights of the stranger," says Deuteronomy, in a statement that presumes that the stranger does, indeed, have rights. The books of Romans and Hebrews call on those who follow Jesus to "extend hospitality to strangers."

The prophets also recognized the plight of the refugee, stated Baden: Isaiah uses language that should resonate strongly with those lawyers who found themselves at international airports last weekend: "Give advice, offer counsel ... Let Moab's outcasts find asylum in you; be a shelter for them."

Baden wrote that the Bible also says that one day the divisions between citizen and stranger will be effaced, when the promised land shall be apportioned "for yourselves and for the strangers who dwell among you, who have begotten children with you" - a sort of biblical Dream Act, courtesy of the prophet Ezekiel.

"Caring for the stranger is not merely something that we should do; the Bible suggests it is what God does," said Baden.

"'He loves the stranger, providing him with food and clothing,' says Deuteronomy. Yet we are not to leave the care of the stranger in God's hands, for Deuteronomy continues: You too must love the stranger.'"