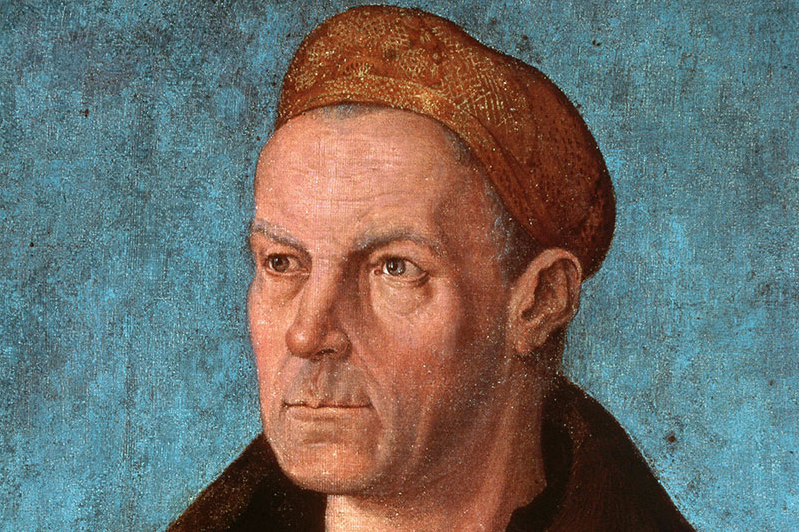

Bankers in modern times have taken a beating in terms of reputation thanks to continuing economic uncertainty around the world. However, one German banker named Jakob Fugger of Augsburg wielded significant influence in the 1500s that led to the fundamental transformation of Christianity.

According to Edward Chancellor of the Wall Street Journal, the bankers of southern Germany were the most powerful in all of Europe during the 1500s. Author Greg Steinmetz wrote a biography on the life of Fugger entitled "The Richest Man Who Ever Lived."

"Like all great fortunes, Fugger's derived from a combination of luck and character," Chancellor wrote. "He was fortunate to be born into a prosperous family of merchants in a city whose position in European trade and finance was ascendant."

Chancellor pointed that the German city of Augsburg, now located in Bavaria, was a "free city" that answered to no feudal overload. Its strategic location placed it "on the trade route between Italy and the Low Countries and close to the great silver and copper mines of the central Europe."

"The Fuggers, along with other Augsburg merchant-bankers, provided loans to local rulers secured with the produce of their mines," Chancellor wrote. "This was a very profitable business."

Larry Getlen of the New York Post described Fugger as "the world's first true capitalist," noting that he pursued wealth "solely for wealth's sake" as opposed to fulfilling a desire to rule, meeting religious destiny, or escaping from poverty. Steinmetz wrote that Fugger's view on wealth was a new concept during his time.

"Fugger created a fortune that, by his death in 1525, equaled 'just under 2 percent of European economic output,'" Getlen wrote, citing Steinmetz. "No other man, no Vanderbilt or Gates, has controlled that pivotal a fortune."

Getlen elaborated on Fugger's legacy on European history.

"He was the first documented millionaire, and the first businessman to compile a comprehensive financial statement for his business," Getlen wrote. "He also created the world's first news service, as a way to ensure he had important information before his rivals, a half-century before the advent of the newspaper."

According to Getlen, Fugger helped fundamentally change Christianity after Albrecht of Hohenzollern turned to him for a loan to fill the opening for the archbishop of Mainz. Albrecht came up with an idea that an "indulgence" from the pope would absolve people of their sins.

"To repay the loan, Albrecht's men decided to use the proceeds from selling indulgences, an idea Pope Leo - who 'understood better than anyone the ability to fleece the faithful,' and who once said, 'How very profitable has been this fable of Christ' - supported," Getlen wrote.

Getlen reported that Pope Leo X wanted 34,000 florins, or about $4.8 million in today's money, for the job. To pay back Fugger's loan, the pope authorized the sale of indulgences that would help pay for expensive upgrades to St. Peter's Basilica.

"The money raised was split 50/50, with half going to the pope, the other half to Fugger," Getlen wrote.

However, Getlen reported that a reformer named Martin Luther was disgusted by the profitability and con job of the sale of indulgences from the Catholic Church. He later wrote "his famous Ninety-Five Theses," which helped trigger a movement in Christianity known as the Protestant Reformation.

"For these reasons and more, Steinmetz makes the persuasive case that Fugger was 'the most influential businessman of all time,'" Getlen wrote.

According to Getlen, Fugger also helped transform the world of finance by convincing the pope to legalize the charging of interest through a decree. Before that time, the Catholic Church considered usury, or charging interest on loans, a sin; now the pope indicated that interest was only usury if the loan was made "without labor, cost or risk."

"Leo's decree was a breakthrough for capitalism," Steinmetz wrote. "Debt financing accelerated. The modern economy was under way."

Getlen reported that Fugger died in December 1525 at the age of 66. An accounting of his business found that his total accumulated wealth was at 2.02 million florins, which was worth hundreds of millions of dollars in today's money.

"Seventeen generations later, during World War II, his descendants were still living off income derived from the business he built," Getlen wrote.

"The Richest Man Who Ever Lived" is now available in bookstores and online.