Based on observations conducted by the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA confirmed on Thursday that Jupiter's largest moon, Ganymede, has a saltwater ocean underneath its icy surface.

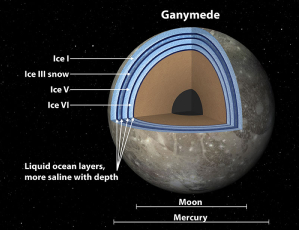

According to Rachel Feltman of the Washington Post, the ocean discovered by the space agency seemed to have more water than all the water on Earth's surface. Scientists estimated that the ocean on Ganymede is 60 miles thick and buried under 95 miles of ice.

"This discovery marks a significant milestone, highlighting what only Hubble can accomplish," John Grunsfeld, assistant administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters, said in a statement. "In its 25 years in orbit, Hubble has made many scientific discoveries in our own solar system. A deep ocean under the icy crust of Ganymede opens up further exciting possibilities for life beyond Earth."

Feltman reported that scientists have speculated since the 1970s about the presence of an ocean on Ganymede, which is the largest moon in the solar system. The Galileo spacecraft flew by it quickly but was unable to stay long enough and confirm whether or not Ganymede had a liquid ocean.

Geophysicist Joachim Saur of the University of Cologne in Germany talked with Reuters about the significance of NASA's latest discovery.

"Jupiter is like a lighthouse whose magnetic field changes with the rotation of the lighthouse. It influences the aurora," Saur said. "With the ocean, the rocking is significantly reduced."

Reuters elaborated on how scientists were able to draw the conclusion that Ganymede may have an ocean underneath its surface.

"As Jupiter rotates, its magnetic field shifts, causing Ganymede's aurora to rock. Scientists measured the motion and found it fell short," Reuters wrote. "Using computer models, they realized that a salty, electrically conductive ocean beneath the moon's surface was counteracting Jupiter's magnetic pull."

According to Reuters, scientists ran more than 100 computer models to determine what could be affecting Ganymede's aurora. Observations from the Hubble were repeated to gather and compare data for both belts of aurora.

"This gives us confidence in the measurement," Saur said.

According to Feltman, the Hubble can study the interior of planets far off in the distance thanks to the telescope's "impressive gravitational analyses." During a NASA news conference on Thursday, Hubble senior project scientist Jennifer Wiseman indicated that oceans could also be detected on distant exoplanets.

"It may require a telescope larger than the Hubble, it may require a new space telescope, but nevertheless it is a tool we have now," Wiseman said.

Astronomer Heidi Hammel of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy commented on the significance of the finding to Reuters.

"It is one step further toward finding that habitable, water-rich environment in our solar system," Hammel said.