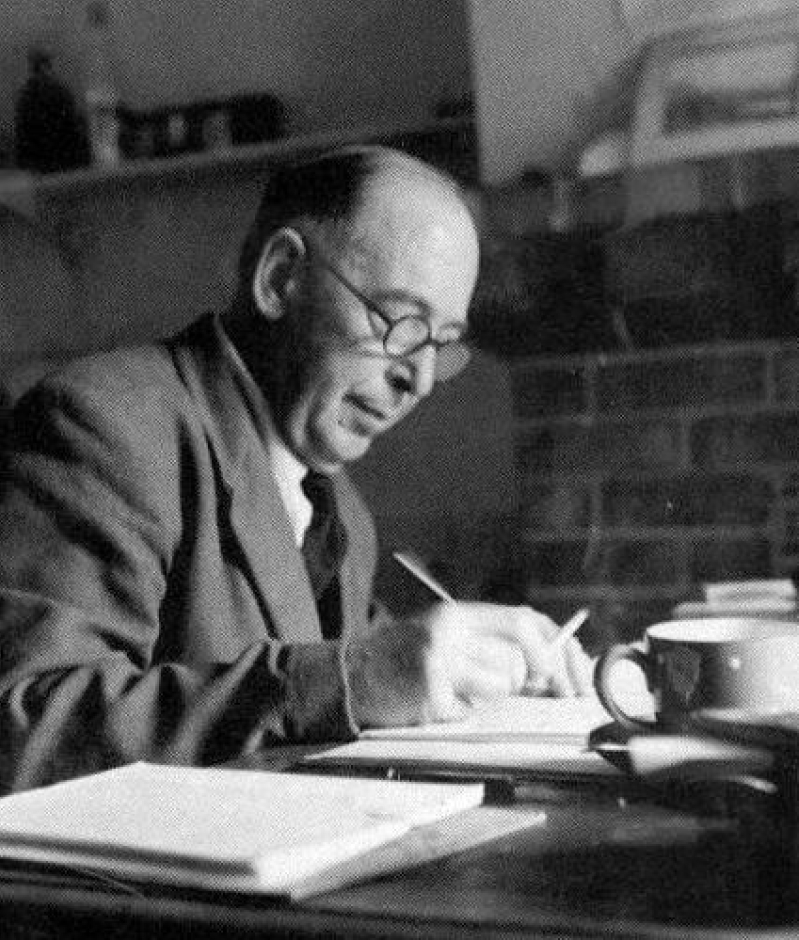

It has been described as a searing of the soul, a rending of the heart. C. S. Lewis aptly called it a "problem." And yet the Bible says that there is no such thing as a Christian without it.

Pain.

Perhaps the most difficult pain, Lewis addresses moreover, is the matter of emotional, or mental, pain:

“Mental pain is less dramatic than physical pain, but it is more common and also more hard to bear. The frequent attempt to conceal mental pain increases the burden: it is easier to say “My tooth is aching” than to say “My heart is broken.”

Since we are only very young, we learn to become quite acquainted with physical pain. It exists even before we cut our first tooth, and, while unpleasant, comes as hardly a surprise as we grow older. Psychological and emotional wounds, no matter how common on the other hand, tend to continually jar us. There never seems to be a remedy powerful enough to ease the tears of anxiety or the burden which wreaks havoc on our blood pressure and digestive tracts. Perhaps this is what Saint Paul identified as the thorn in his flesh; perhaps each Christian, individually, must struggle with such a thorn.

Likely, the greatest obstacle to accepting Christianity is this very subject. Men such as Charles Templeton and Richard Dawkins, some of the most renowned atheists of the modern age, could not comprehend a God who allows bad things to happen to good people. Yet the Bible attributes two reasons for the problem of pain. First, the reality of sin. At the Fall, perfection dissipated into a spiral of degeneration. Second, the reality of God's mercy. Scripture directs to the reason of prolonged pain at the hands of merciless men. He is very clearly patient with all and desirous of their repentance (2 Peter 3:9). How very important it is, then, that we as Christians face the problem of pain with a drastically different view than our unbelieving fellows in humanity.

Dear Lewis gave further insight as to the association of people and pain:

"For you will certainly carry out God's purpose, however you act, but it makes a difference to you whether you serve like Judas or like John.”

Very simply, how we react to the "problem" reveals us as either a Judas or a John. Of course, "dealing" in no way means denying our humanity. To do so would not be a holy endeavor, but an attempt to paint us more God-like---in actuality, an affront to our Savior and an elevation of pride. After all, Jesus Himself wept drops of blood, Ezra tore out his beard, and Mordecai lathered himself in ashes. Sin, in addition, will always be an appendage in every endeavor of holiness. What distinguishes Judas and John, in the end, is not the sin nor even the season of despair, but the outcome. Peter describes it as a mysterious tool by which we are saved and sanctified:

"And the God of all grace, who called you to His eternal glory in Christ, after you have suffered a little while, will Himself restore you and make you strong, firm and steadfast (I Peter 5:10)."

Again and again, Scripture recalls the significance of perseverance. This perseverance is not something that we attain in and of ourselves, but exists an act of obedience in response to a divine act of grace. I wonder if, as you read this, you are discouraged by the feeling that God has abandoned you. If you're a believer, Christ has promised never to leave you nor forsake you (Hebrews 13:5), I can assure you. No, pain is a matter hinging on the open door of restoration and hope. We are here for a little while in order to conform to His image and, thereafter, enjoy His Glory forever.